In 2009, I was struggling with a prompt I’d been given in a writers’ class. I needed to write a scene in which a woman rejected a very persistent man who’d asked her on a date.

In 2009, I was struggling with a prompt I’d been given in a writers’ class. I needed to write a scene in which a woman rejected a very persistent man who’d asked her on a date.

I began with a guy trying to ask out a coworker. He knows she has a boyfriend, but thinks that he mistreats her. No matter how I approached the scene, it felt clichéd, lacked substance, and just wasn’t working.

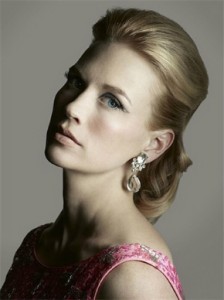

A couple of nights before the assignment’s due date, I turned on Netflix. I needed a break from thinking about how to tackle my homework and saw that season one of the AMC period drama “Mad Men” was available as streaming video. I’d read from many different sources, including former Curtis Brown literary agent Nathan Bransford’s blog, about how groundbreaking the show was. Many reviews praised its accurate portrayal of the 1960s.

I was stunned. The acting and writing truly were incredible, and the show deserves every accolade and award it’s received. What I wasn’t ready for was the up-close-and-personal scenes of outright bigotry, chauvinism, sexual harassment, and all-around depiction of how women were treated.

My main sympathies were with Betty Draper, the archetypal housewife played by January Jones. Everything from her numb hands to her patronizing psychiatrist and her heavy-hitter executive husband Don Draper cheating on her left me cold.

The pivotal last scene of the first episode will forever be imprinted in my mind. After depicting a typical day in the life of Don, who works for Sterling Cooper Advertising on Madison Avenue in New York City, the camera follows him returning to his picturesque suburban home. His beautiful wife waits up for him and his two children are tucked snuggly into their beds, asleep. This is a stark contrast to the beginning of the episode, when we see Draper having an affair with a young bohemian woman who could be a Greenwich Village resident, totally unlike his wife.

I kept watching the season one episodes, hoping to see one of the office girls or even Betty Draper achieve a huge personal win. None of the female main characters became their own heroes though. Not even Rachel Menken, the heiress of Menken’s, a major department store in New York City, proved immune to the outright sexism in the show. Although the female characters acknowledged their abuse, no one really stood up to the mistreatment and chauvinism in the office and at home.

Waiting for the female characters to ditch their passivity became a horrible itch that I couldn’t scratch.

I came away from the episodes with unsettled feelings and looming questions. Were women really treated that way in the late 1950s and early 1960s? If this was an accurate portrayal, why didn’t anyone feel compelled to stand up to the harassment?

I didn’t like her answer, but as I digested her words I realized they couldn’t ring truer. That’s exactly the attitude depicted by the “Mad Men” women. Many of the girls in the Sterling Cooper office and Betty Draper just normalized the treatment, keeling over, resigning themselves to be handled as objects, and serving their men because that was the way it was.

This patriarchal world didn’t really fit my idea of the late 1950s and early 1960s. Many people, including me, have an idyllic perception of this era. With mostly television and film as my guide, I believed it was a magical time when family values were a priority, a sense of community was important, and everyday glamour pervaded the culture. Women and men cared about their appearance, and dressing up was the norm. All the women were happy housewives baking pies and waxing floors for Mr. Wonderful, while taking care of their darling children.

The “Leave it to Beaver” Family

Until 2013, I’d never been exposed to Betty Friedan’s book “The Feminine Mystique” nor “Sex and the Single Girl” by Helen Gurley Brown. These two seminal works were in part responsible for ushering in the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s and 70s. So, regrettably, I was a real newbie coming to all of this information.

Looking back, I remember that women’s suffrage was covered in high school history, but not women’s liberation. I also did not take a women’s studies course in college, as that was not a requirement. During November 2013, I asked two women, both in their early twenties, if they knew anything about the history of women’s lib or if it was covered in college or high school. They both said that it wasn’t taught in-depth and that the primary focus in their history classes was on women’s suffrage.

Their experience sounded very familiar.

For those who don’t have much background knowledge on the history of feminism, the first wave primarily focused on suffrage, the right to vote in elections. It began in the 19th century and culminated with passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1919. Overturning sexist laws, like the prevention of women owning property, was also a focus.

The second wave started in the 1960s in the United States. This movement targeted a broader range of issues than the first. Concerns regarding reproductive rights, sexuality, family, workplace, and other areas where disparities between the sexes were legal became the focal points. Thankfully, many women’s tireless efforts of standing up to the status quo helped create: institutions like rape crisis clinics and battered women’s shelters, legislation outlawing marital rape, and changes in custody and divorce laws.

The second wave started in the 1960s in the United States. This movement targeted a broader range of issues than the first. Concerns regarding reproductive rights, sexuality, family, workplace, and other areas where disparities between the sexes were legal became the focal points. Thankfully, many women’s tireless efforts of standing up to the status quo helped create: institutions like rape crisis clinics and battered women’s shelters, legislation outlawing marital rape, and changes in custody and divorce laws.

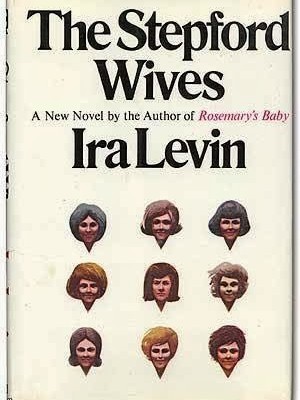

The 1976 film adaptation of Levin’s book “Stepford Wives” was my first in-depth look at the satirizing of the “perfect housewife.” Levin’s thriller was written in 1972 but it harkens back to the 1950s’ Great Suburban Boom. The film centers on the main character Joanna Eberhart’s efforts to solve the mystery of why women in her sleepy town of Stepford look perfect and have immaculate houses, but seem oddly…robotic.

Like my later reaction to “Mad Men,” I came away unsettled by its thought-provoking depiction of women, yet at the time I didn’t really explore the history and meaning behind Levin’s story. After digesting the scope of Levin’s work and the episodes of “Mad Men,” I knew I had the inspiration I needed to write my scene. I set it during the early 1960s and the women of “Mad Men” were in the forefront of my mind as I wrote.

The more I studied, the more I was shocked to find just how unhappy many women were with their domestic roles. I discovered many tragic stories of women as victims in a male-dominated society. Divorce settlements were rare and in many states non-existent. It was also nearly impossible to prove abuse. Laws to protect women as individuals with basic human rights were few and far between. Like Peggy Olson’s character in “Mad Men,” some women were even sent away to have out-of-wedlock children. And if you were impregnated at a very young age, you were often shipped off to a nunnery.

In 1963, journalist Betty Friedan spotlighted some of these issues. “The Feminine Mystique,” written by Friedan, originated with the results of a survey she’d conducted during her 1957 college reunion. The questions focused on overall satisfaction with the graduates’ current lives as housewives and found that many were unhappy with their situations.

Betty Friedan

Friedan’s claims and opinions were met with an initial backlash and sparked an all-out war over women’s traditional roles. Many people dismissed her as a disgruntled housewife. However, it wasn’t long before Friedan’s message gained momentum and ushered in the second wave of women’s liberation.The late 1960s became a time of uncertainty over the fate of The American Dream. For good or ill, the white-picket-fence utopia built around a woman dedicating her life to being both housewife and mother seemed under siege.

As Betty Friedan says about women during that era, “They did give up their own education to put their husbands through college, and then, maybe against their own wishes, ten or fifteen years later, they were left in the lurch by divorce. The strongest were able to cope more or less well, but it wasn’t that easy for a woman of forty-five or fifty to move ahead in a profession and make a new life for herself and her children or herself alone.”

As Friedan alludes to above, men primarily held the financial resources in society during this period. Women gained access to these means either through birth or marriage. It was not uncommon for women to marry in order to acquire a home, and many attended college for the sole purpose of earning their “MRS” degree, which meant finding a husband.

Also, as in Jane Austen’s time, it was widely accepted that a woman’s place was in the home. The advertising campaigns in the 1950s and 1960s evidenced the same ideal. Many women are shown looking glamourous while preparing meals, vacuuming, and performing other miscellaneous domestic tasks. Perfect dolls in perfect playhouses. Similarly in Austen’s era, the image of the standard perfect mother was one who was selfless, doing anything for the good of her family.

Historian Dr. John Bladek pointed out to me that this common depiction of the domesticized wife was popularized until the 1920s but faded somewhat during the Depression and especially during World War II. During the war, women were encouraged to get jobs to help the war effort, since so many men had gone overseas to fight.

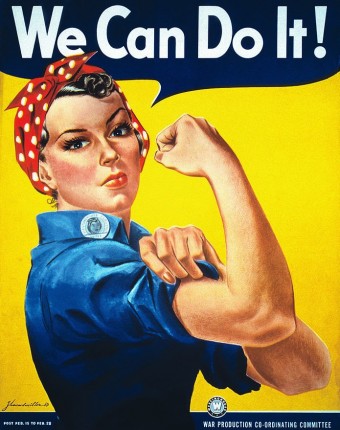

Rosie the Riveter

After the war, the returning soldiers needed their jobs back, so the image of Rosie the Riveter got shelved and the idealized housewife persona was revived and restored through advertising, which was mostly a male dominated profession (powerful stuff that advertising, eh?).

Also, after World War II ended in 1945, the government-funded G.I. Bill spurred a boom of men attending college. According to the “Mad Men” documentary “Mad Men: Birth of an Independent Woman,” women were made to feel ashamed for taking up seats in colleges. These seats, it was thought, rightly belonged to returning veterans. Men were given first priority because it was their traditional role to provide for a family.

Many women ended up leaving school or didn’t attend in the first place to accommodate their male counterparts. While more women attended college in the 60s, this self-sacrificial attitude was carried through to the next generation and was evident in other areas such as the instruction manuals on how to be a “good wife” that circulated throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

There were even pamphlets that demonstrated how to sexify this self-sacrificing domestic role. Women were shown how to properly greet their husband upon his return from work. It was important to freshen up, apply makeup, and have a cool drink and hot meal ready for him as soon as he walked through the door.

If anything, it’s easy to see that the view of women only as reproductive/sexual/domestic beings was concentrated in the mainstream media. Societal norms and propaganda at the time portrayed a woman who rejected this domestic lifestyle as odd and unappealing, destined to die an old maid.

“Mad Men” cleverly depicts these kinds of attitudes and the widespread depression and anxiety many women experienced because of these expectations. Yet women often hid their suffering to maintain the image of the perfect house and perfect family. Like a cheating husband, an unkempt home and naughty children were a woman’s fault. Depression was an unspeakable failure. Some women turned to pills like Valium to help get them through their days, which is illustrated in the 1966 Rolling Stones’ song “Mother’s Little Helper.”

It’s clear now that many middle-class women struggled with their limited role, which required them to be martyrs and primarily focus on others. On a deep level, female-kind was missing some of the balance and fulfillment that an education, career, or pursuing their own interests could bring to their lives after marrying.

Upon learning all this, it made sense for me to pin down a date for “Seeing Red.” I set it in early 1962, a year before Friedan’s “Feminine Mystique” was released. I wanted a world in which there was little—if any—public acknowledgement that the status quo was highly flawed in order to make the main character Bridget’s struggle that much harder. Sometimes it’s so difficult to differentiate what’s right from wrong when the culture you live in tolerates or encourages inappropriate behavior. I wanted that conflict demonstrated in Bridget’s thinking.

Upon learning all this, it made sense for me to pin down a date for “Seeing Red.” I set it in early 1962, a year before Friedan’s “Feminine Mystique” was released. I wanted a world in which there was little—if any—public acknowledgement that the status quo was highly flawed in order to make the main character Bridget’s struggle that much harder. Sometimes it’s so difficult to differentiate what’s right from wrong when the culture you live in tolerates or encourages inappropriate behavior. I wanted that conflict demonstrated in Bridget’s thinking.

In “Seeing Red,” Bridget eyes are opened to societal problems that need to be identified and ultimately addressed. Her character represents a herald of change that would come with the second wave of women’s rights.

It’s challenging writing historical fiction, as an author wants to strike a balance between being as accurate as possible while making the story accessible to modern readers. I wanted to bend one historical norm regarding the main character: Bridget is not meant to be a completely exact portrayal of an average woman in her early 20s in 1962.

Most women probably wouldn’t have had the confidence to speak up or walk away when faced with the relationship challenges demonstrated in “Seeing Red.” I didn’t want to write about an average woman—I wanted a heroine who could quietly stand up to the conventions of the times. Then I could finally scratch that itch from watching “Mad Men.”

Whenever I could, I’d take the opportunity to talk with women who lived through the era and would be amazed to hear of the difficulties that seemed to be a shared history among them all.

One woman I spoke to was brave enough to tell me she’d gotten pregnant in the late 1950s as a teenager. The pain in her eyes as she recounted the story of shame from living as a societal outcast still seemed very fresh.

After listening to all the stories in combination with my research, I was very grateful for all the women in history who were brave enough to speak out against gender inequality and who continue to do so to keep us from going back to a pre-women’s lib world. As I worked on this project, one theme developed: Favoritism of a specific gender in any society or organized group has devastating consequences.

On that note, some of my readers may notice another underlying theme in “Seeing Red” and my New Adult novel “Scarlette.” Like “Scarlette,” Perrault’s “Little Red Riding Hood” premise infuses “Seeing Red:” A naïve girl up against big bad wolves whom she suspects are safe people but who are ultimately ready to “devour” her. “Seeing Red” is a thin, modern version of the tale with real “big bad wolves,” rather than a historical “wolf” like the Beast of Gévaudan in “Scarlette.”

I initially wrote both of these stories around the same time, which may explain the recycled themes of the Red Riding Hood archetype, but really, the girl in the red cloak seems to be everywhere, even in the roots of the history of feminism (life imitates art, I suppose).

Famous writer and director Alfred Hitchcock probably put it best when he said, “Nothing has changed since Little Red Riding Hood faced the big bad wolf. What frightens us today is exactly the same sort of thing that frightened us yesterday. It’s just a different wolf.”

“This [Seeing Red] is a compelling tale of self-determination set on the cusp of the women’s rights movement. Think Mad Men told entirely from a woman’s perspective.”

—Matthew Rovner, Screenwriter of “Elysium: The Last Ark

Leave a Reply